This winter, the weather has been much more like what I remember growing up than anything we’ve experienced recently. Mornings began to get cool in August, the daytime highs fell steadily in September and October, and it was consistently cold by November. There has been enough snow to cancel school three times in December and January, and we have had two weeks of temperatures between zero and fifteen degrees with cold northerly winds. You know, the kind when weathermen begin instructing viewers about survival techniques, or, “Don’t be a moron and wear flip-flops today because you think it’s cute.”

(Moron.)

One person at work called this winter a “gut punch.” Hard to believe, because this person has lived in New England all of his life, including many years before Al Gore invented the Internet to tell people about global warming.

(“You laugh now, buy one day people will be wearing flip-flops in January.”)

(“You laugh now, buy one day people will be wearing flip-flops in January.”)

The monumental discomfort of those around me made me think back to the most uncomfortable I’ve ever been because of the weather. This happened last summer, and it happened during the second greatest thing I’ve ever done, after climbing to the top of a mountain in a foot of snow to get married. More on that later. Maybe.

My friend Stephen and I have had many adventures over the years involving model rocketry, tennis, and especially astronomy. We have fought fog, freezing temperatures, and marauding mosquitoes to see meteor showers. Massachusetts state troopers have descended upon us for setting up a telescope next to a pasture.

(“How do I know you’re not escaped felons?”)

(He really said that.)

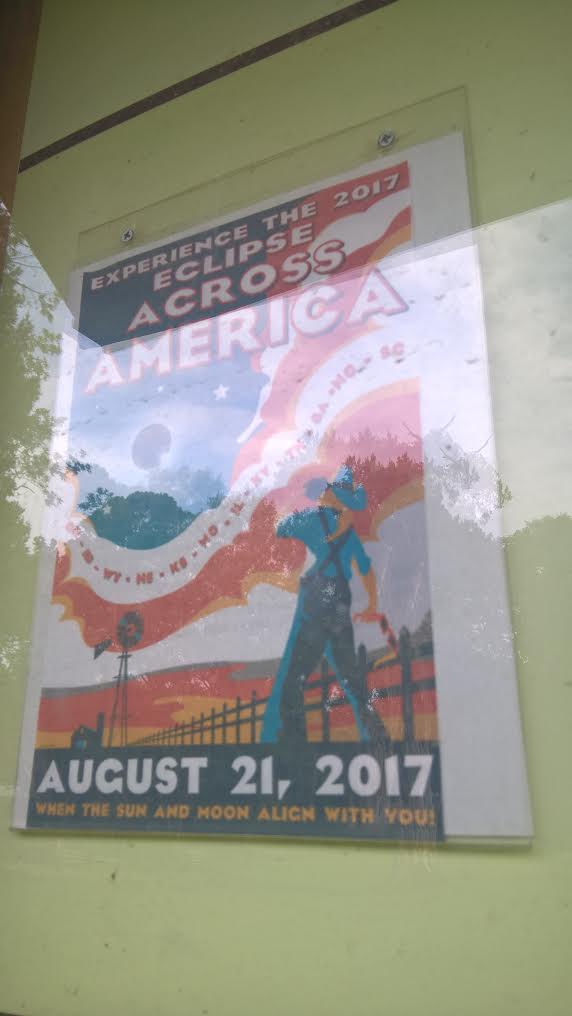

We have used old aerial reconnaissance lenses to see all of the Messier object in a single spring night. We have collected spectra of a space probe smashing into a comet. We have plotted the infinitesimal dip in a star’s light as its planet passed between us and the Earth. But last summer, we decided to travel to the path of totality for the Great American Eclipse on August 21st.

The event had been on my radar for almost two years, ever since Sky and Telescope magazine ran a feature in January of 2016 advising astronomers to plan ahead. They said that people were already making reservations to stay near spots along the path of totality nationwide. I looked at a map of the track, running from Oregon to South Carolina, and resigned myself to seeing a partial eclipse from home. After all, we would need to drive if we wanted to bring our own equipment, and we lived at least three days by car from the nearest point of totality. That’s quite a commitment when the entire event can be ruined by a quirk of August weather.

As the summer progressed, though, I began to feel the urge to end it with a bang. Why go gently into the end of vacation? I knew Stephen loved driving, and often took long road trips to see different parts of the country. Why not make this a week-long adventure that might or might not contain a total eclipse?

His first reaction was somewhat less than enthusiastic. After all, the date was quite close to the start of the academic year, and he’s a high school science teacher. Because he takes his job seriously, he ordinarily uses the time to prepare for the upcoming campaign.

(“I don’t need no education.”)

By the next day, though, he had completely changed his tune. What better preparation could there be for nine months of adolescent posturing than to out-fun the youths? Over the course of a single drizzly afternoon (with the Little League World Series playing as background), we put together a six-day odyssey. Its outbound leg would stop in Maryland and North Carolina before arriving in South Carolina on Sunday to scout out potential locations near Charleston for the big day on Monday. Instead of my pickup truck, we opted for his parents’ old minivan, which would keep our telescopes and cameras and tent dry if the weather turned foul, as well as offering emergency sleeping options for us. As an afterthought, he warned me that the air conditioner was not working. This is for science, I thought. How bad could it be?

We drove about eight hundred miles, pretty much due south to southwest, during three blindingly-sunny days in August. If you have never quite understood how a greenhouse works, try this sometime. Open the windows at highway speeds? That just moves hundred-degree air around. (Not to mention making it quite difficult to listen to an audio book. Imagine listening to Richard Feynman talk about the Manhattan Project at volumes that would make The Who put in earplugs.) Spend two hours stopped dead in traffic on the Delaware Memorial Bridge and you can actually feel the muscles in your legs slowly roasting.

As we progressed south, even the nights stayed unbearably hot. Camping at a national forest in North Carolina, I slept without covers intentionally for the first time in my life. I wore no shirt, but my sweat could not evaporate into the still, saturated air. Worse, step out of the tent for a breath and the horse flies descended as if we were road kill. If we ventured down to the water to dip a toe in, we risked walking through the webs of these guys.

The webs could stretch between trees ten feet apart. The spiders themselves were up to six inches across, and somehow not as cute as the tarantulas I could outrun when I lived in Tucson. When I woke up, I tried to take a cold shower intentionally for the first time in my life, but the water from the well was lukewarm.

During the entire journey south, I had the distinct impression that someone was poaching me like an egg. The ten-minute sojourns into Wal-Marts (Wals-Mart?) and air conditioning only made it worse. I will never know how any Union soldiers survived, let alone won any battles, in the Civil War.

(“I did it while wearing wool.”)

In order to give us the best chance of seeing the eclipse cloud-free, we looked for spots along the coast. Historic weather patterns indicated that off-shore breezes were likely to blow any afternoon clouds a few miles inland and facilitate the view. We spent several hours cruising up and down Route 17, finding out where we could legally set up as close as possible to the center line of totality. A state park ranger at a former plantation site told us he expected his parking lot to reach its 800-car capacity within minutes of opening at 9 AM for an event that would only start four hours later. Sites on the beaches that were holding ticketed viewing events were already sold out. We decided our best bet was to find a school or church parking lot, and settled on a middle school tennis court in McClellanville. Still, where were the millions of sungazers everyone had told us to expect? There were even vacancy signs on hotels! On the way back to our camp, we spent a triumphant hour body surfing at Myrtle Beach,

(the beach part, not the mall)

convinced that we had positioned ourselves for success.

The next morning, we had our complacency rudely shaken out of us. As soon as we got on the road, we found all of the people who had not been in evidence on Sunday. Bumper-to-bumper traffic stretched as far as we could see, and all of the license plates came from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and other points north. We began to wonder if we would get to our spot in the four hours we had, and if there would be any space for us when we got there. Worse, as we sat, the clouds became solid overcast and started to rain on us. Last night, the Clear Sky Clock had indicated only partial cloud cover for the 2-3 PM hour. Now, it indicated nothing but overcast. Our coastal breezes plan had backfired, and all of the previous day’s planning was wasted. But forecasts for some inland locations looked more promising.

We looked at each other and knew what we had to do. Pulling out a paper map from AAA ( yes, they do still make paper maps, and we would not have been able to pull this off without one) on which we had drawn the path of totality, we turned northwest at Georgetown and began our eclipse chase. Think of those time-is-running-out-because-the-danger semi-documentaries where two guys in a van chase tornadoes across Nebraska. Stephen had our map, a cellular telephone, and a laptop computer in the passenger seat trying to determine how far we had to go away from the coast to have time to set up and a decent chance of actually seeing anything. I drove, perhaps faster than I should have, constantly scanning the horizon for clear sky and police. When we entered a downpour which turned into a lightning storm, I was convinced that all was lost. No, Stephen assured me, this was the last band of clouds. If we got within a couple of miles of Interstate 95, we would be in the clear.

Sure enough, the storm passed and we finally drove into bright sunlight with a few puffy fair weather clouds scattered about. Better yet, the roads, parks, fields, and parking lots were empty. It seemed that everyone had headed for the coast. And, apparently, disappointment. As Stephen continued to navigate, I worried that we would pass up good spots in search of perfection, then need to waste time backtracking. On the outskirts of the town of Manning, I suggested we find a place to set up, since we now had less than an hour to go before the Moon entered the Sun’s disk.

Stephen agreed, located the town’s high school (for the open athletic fields), and directed me to it. Then, as we approached, my heart sank. The place was packed. The parking lot was full. The school band was playing. People were lounging and dancing. Had we taken a wrong turn at Albuquerque and wound up at Burning Man?

(“What’s up with the crowd, doc?”)

I was on the verge of asking if we could turn around and pick a deserted parking lot outside of town when Stephen preempted me by locating the middle school as a separate point on the map and suggesting we try there. We did, and found this.

Sorry about the exposure, but that’s not the important part. WE HAD THE ENTIRE PLACE TO OURSELVES! And there was not a cloud anywhere near the sun. We’d done it! We began unpacking and setting up our equipment with forty-five minutes to go before the first contact of the Moon on the Sun. We could now relax and enjoy our first total eclipse.

Or could we? As I began looking through my filtered telescope at the Sun, a car drove into the parking lot. Oh, no; here we go again. Remember, many of my astronomical experiences involve the arrival of police with instructions to pack up and move along.

Not this time. A (non-police) man walked over and said, “Howdy, fellas. I’m J. D. Evans. Who all are you?” We introduced ourselves and waited for the hammer to fall. “My wife’s the secretary here at the middle school.” Yup. He’s going to tell us we’re not allowed to be here. “Our family is going to be over at the eclipse party next door.” Damn! We’re trespassing and we’ll need to move. Can we do it in time? “We wondered if anyone had discovered the junior high. Do you have everything you need? Can we bring you a cold drink or something?” Hey, I think he means it. You know, this is the first time on the trip when I did not notice the heat bothering me. We assured him we had fruit and plenty of water. “Great! Well, I’ve got to take my family back to the high school. We’ll check back on you later.”

That was it. No cops. No charges. No frenzied relocation. Just the friendliest guy either of us had ever met.

At 1:15, I saw the Moon’s silhouette take its first bite out of the Sun’s image. It was really on! I called my wife and daughter to make sure they were watching at home and then got back to business.

About fifteen minutes before totality began, another car drove up (NOT NOW!) and out climbed a young couple with four little children (much relief). They had done a family art project making their eclipse viewing glasses into monster masks. It was adorable! Despite being incorrigible introverts, we ended up chatting with them about our trip and the day, showing them the view through our telescopes, pointing out how small gaps between the leaves on trees made hundreds of pinhole eclipse viewers,

marveling at totality,

and generally enjoying their company. I guess I don’t hate all people, just large crowds of them. It was over all too quickly, but it was worth every moment of heatstroke and anxiety.

Right on cue, J. D. Evans returned to see how we had fared. He really did just care whether we had enjoyed ourselves in his town.

Yes, Mr. Evans, we did. The day, the place, and you were all perfect. Thank you.